Body Sites for Temperature Assessment

Body Sites for Temperature Assessment

An Overview of Temperature Measuring Sites

Oral Temperature

Oral temperature measurement is by far the most common clinical method in use today, and

is responsible for masking the greatest number of fevers. Oral temperature can be mislead-

ingly lowered by patient activity such as tachypnea, coughing, moaning, drinking, eating,

mouthbreathing, snoring, talking, etc. Alarmingly, another cause of low oral temperatures is

the fever itself. For each 0.6°C (1°F) temperature elevation, the pulse rate usually increases

approximately 10 beats per minute, there is a 7% increase in oxygen consumption, increas-

ing the respiratory rate approximately 2 cycles per

minute. The resulting increase in respiration can further

lower oral temperature sufficiently to mask a fever.

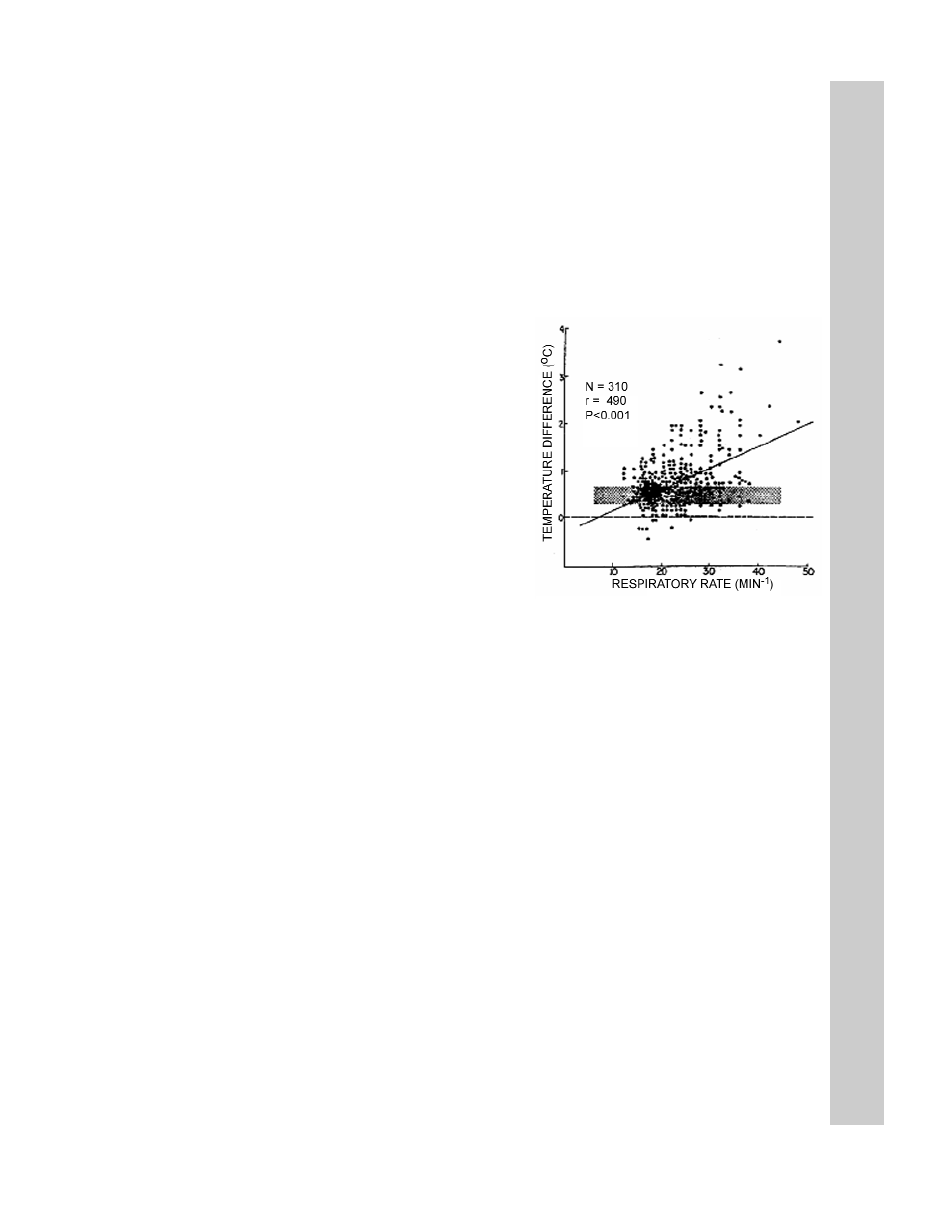

Figure 1 is of interest as it illustrates fever masking even

when clinicians had eliminated all obvious mouth-

breathers from the study. This emergency room study

presents the temperature difference (rectal minus oral) in

310 patients with a wide range of respiratory rates. The

straight line of best fit is shown. The stippled area

demonstrates the traditional normal difference between

rectal and oral temperature (0.3°- 0.65°C). The investi-

gators concluded that many patients with tachypnea

would have oral temperatures in the normal range

despite the presence of clinical fever, seriously mislead-

ing the clinician.

Rectal Temperature

Generally, rectal temperature is considered an indicator of

deep tissue and critical tissue temperatures, but long standing data demonstrate that rectal

temperature can be a lagging and unsatisfactory index. Fifty years ago, Eichna et al reported

differences between intracardiac, intravascular and rectal temperatures on afebrile patients to

be so insignificant that for all practical purposes, the temperatures may be considered to be the

same. Certainly rectal temperature is far less invasive than a pulmonary artery catheter, how-

ever, in the same study, data on febrile patients support sizeable differences.

Other comparisons between rectal, esophageal and aortic temperatures undertaken on

hypothermic patients by different researchers also confirm similar differences. Subsequent

but equally comprehensive comparisons on healthy volunteers further confirmed not only

temperature differences, but also quantified significant lags in rectal temperature vs. hypo-

thalamic temperature by times of order one hour. This is of interest since the blood as it

enters and affects the critical tissue in the hypothalamus should have considerable signifi-

cance in thermal homeostasis. However, this early data on hypothalamic temperature was

measured by a thermocouple inserted against (and often times perforating) the tympanic

membrane. With significant improvements in the methodology, more recent clinical observa-

tions show that the time constant of rectal temperature in critically ill patients may be consid-

erably longer, and in some cases, as much as a day.

Figure 1 Temperature Difference (Rectal

minus Oral) in 310 Patients with a Wide

Range of Respiratory Rates. The straight

line of best fit is shown. The stippled area

demonstrates the traditional “normal” differ-

ence between rectal and oral temperature

(0.3 to 0.65°C).

17

818528r5:818528r5.qxd 4/24/2008 11:04 AM Page 19